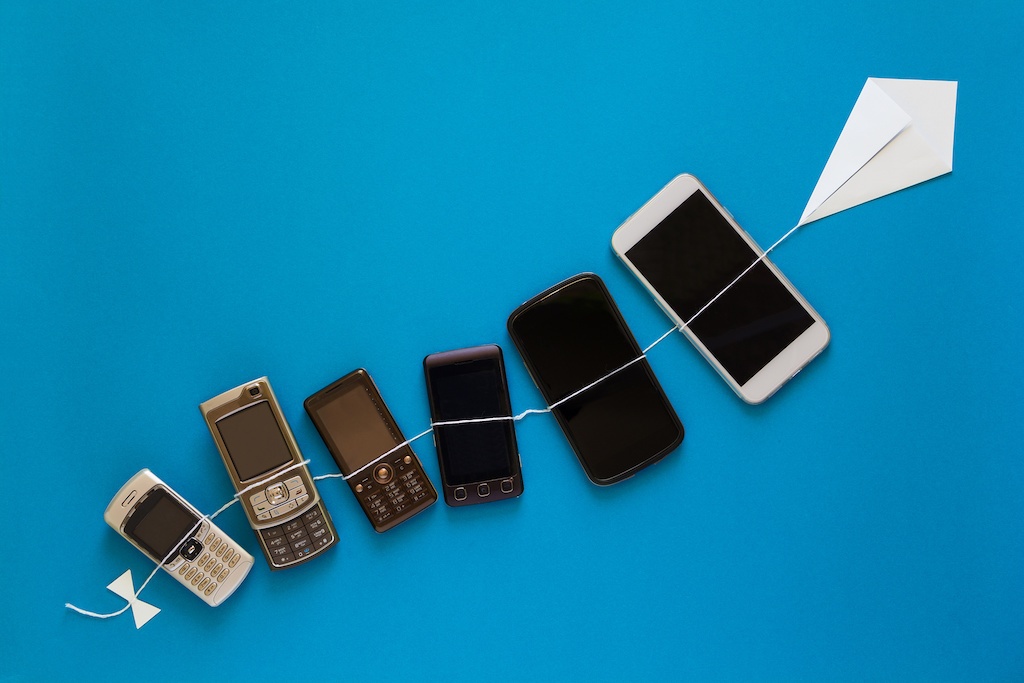

Product management is a relatively new discipline, but its roots range back nearly a century. Understanding the history of product management and how it’s going helps navigate the weird liminal space we often find ourselves in.

The need for product management, however, isn’t new. Like most innovations, people didn’t realize they needed it, and instead, they relied on some awkward workarounds. But then product management finally evolved into a mature, well-defined going concern.

ProductPlan’s own VP of Product, Annie Dunham, recently looked back at how product management came to be in its present form and its unnamed-yet-pervasive presence in her own childhood.

A Brief History of Product Management: Starts With a Spark

As long as people have been people, there has been a market economy to get them what they need. Hunters needed to kill a wooly mammoth, so someone made them a spear in exchange for an extra piece of mammoth tartare or a spare pelt. Farmers swapped crops to diversify their diets. Traders exchanged goods. Laborers labored for a loaf of bread or a bit of precious metal.

As our markets evolved and currencies took hold, commerce replaced barter and trade. People became buyers or sellers, depending on the circumstance. Then sellers learned that if they offered more things people actually wanted, they sold more stuff. Larger merchants realized that they must identify what buyers really needed so they could sell even more.

But it wasn’t until the 20th century that the biggest brands in the world got their arms around the idea that customer’s mental and emotional approach to commerce actually mattered. With so many competitors offering similar products, it wasn’t good enough to only sell “soap.” Instead, you needed to understand why people were buying soap, how they used their soap, what they liked and disliked about different soaps.

Then you could sell the kind of soap they liked and play up the positive attributes in your sales pitch and marketing and advertising. Thus was born the “Voice of the Customer.”

Procter & Gamble introduced this concept in 1931 when they began hiring “Brand Men.” Their whole job was to understand VOC and what problems customers are trying to solve for these individuals.

“It’s fascinating that until the 1930s, this wasn’t even a topic,” Dunham added.

From “Why” to “How”

The next important step in the evolution of product management happened far from P&G’s Cincinnati headquarters. Japan was where product management leaped, informing what to make to how to make it as well.

“Toyota rocked the manufacturing world. They walked in and said, ‘how we’re doing things isn’t great,” Dunham said. She noted that this was when Kanban was created to make delivery and development more efficient. “It becomes even more important to understand what the customer wants and when they need it because that influences their entire build cycle.”

Using this Lean methodology, Toyota created efficient design, manufacturing, and logistics processes. Relying on things like just-in-time procurement and inventory management, they could decrease costs by cutting waste and react to market demand and new technical innovations while building products focused on customer satisfaction and delight.

Product Management Becomes Pervasive Yet Misunderstood

In the second half of the 20th century, many businesses applied product management principles to their business operations. But the process was not described as such. Instead, the process lumped into the broad umbrella of “Marketing.” Through marketing, brands kept upping their investment in understanding consumer needs, the customer’s journey, and the path to purchase.

A Crash Course in Product Management

For Dunham, she was unwittingly receiving a crash course in this discipline by chance. This chance was all thanks to her own father’s job at Walgreens, one of the big three American pharmacy chains. She remarked that her father asked her what she actually does for work, but says “I find this particularly frustrating because, the best I can tell, is my Dad was actually doing product work during his 30-year career at Walgreens.”

Dunham recalls the stories he would tell at night about improving inventory moving through the stores and her embarrassing tagalong trips to those same stores where her father spent the whole time chatting with everyone.

“He was absolutely obsessed with talking to store managers and shoppers,” Dunham said. “It was mortifying as a teenager to go into a Walgreens with my Dad. He knew most of the people working there and wanted to talk to them. But he also wanted to talk to everybody who was shopping too. He wanted to find out what their journey was through the store and why they were stopping to buy things.”

But given his familiarity with product management concepts, if not the terminology, there was still a disconnect between his own work and that of his daughter.

“The reason my Dad doesn’t understand what we do at ProductPlan is that roadmapping wasn’t done that way,” Dunham said. “Their roadmap was a slide that said ‘this is what we will deliver, and it is delayed.’”

Product Management Levels Up With Agile

Products were dead on arrival because they didn’t actually solve customer problems. This problem became increasingly problematic as technological advancements increased their pace. It was cheaper than ever to innovate and bring new products to market, but that wasn’t leading to universal success and on-time delivery.

“This was such a pervasive problem that it led to the Agile Manifesto in 2001,” Dunham continued. “We needed to do for software development what Toyota did for manufacturing. How do we get the risk earlier, move faster, and ensure we’re delivering that value as fast as we can, at the right time when the customer needs it?”

Agile doesn’t work without strong product leadership. Strategic alignment and product roadmaps give engineering enough direction and detail to “be Agile” in their development and delivery. In a world without product management, engineers waste time trying to decide if they’re solving the right problem.

“Here we see a transition from product sitting in marketing to also sitting in Engineering, and there’s a little bit of a hybrid there in terms of those roles sit,” Dunham said. “Product plays a supporting role across these departments. It’s a checks and balances system, and people can get the information they need to go out and do their jobs well.”

It comes down to a return on time. Two-thirds of engineers believe clearer prioritization, responsibilities, and long-term product goals would improve their productivity. Product management can be the single source of truth. It can serve to bring information from various sources together, so everyone’s on the same page.

Lack of alignment means wasting work. But when everyone’s speaking the same language, they can spend their time on bigger problems. Additionally, the whole team can contribute to finding opportunities and identifying risks.

A Home of Their Own

The reverberations from this seismic event continue as product management “grows up” into its own separate discipline.

“Now we see a lot of product management organizations in and of themselves,” Dunham said. “As a result, they have more of a supporting role, they have more information they have to make sure is getting into the right hands, at the right time, and they’re fully dependent on people trusting them and their credibility. They’re not selling the product, and they’re not supporting the product.”

Despite product management getting their own teams and some practitioners climbing the racks and reaching the C-suite, it’s still early days for the role product can play in many settings.

“How product work is done is continuing to evolve,” Dunham continued. “It’s new, and many businesses are slow to adopt change. This is why we’ve seen such a boom in the roadmap industry because the roadmap starts to become the centers to have these conversations.”

Dunham does, however, caution as the history of product management continues not to get too full of itself and realize it plays a vital-yet-complimentary role.

“This is not to show that product managers are the center of everything. We’re not. We’re actually far from it, and we have some humility,” Dunham said. “But we do have a perspective on the user experience, the opportunities and constraints of the technology, and what the business needs.”