When you first learn product management, the terminology can get quite confusing. A couple of terms that the product management world introduced to the software product development domain are outcomes and OKRs. Since those two terms are used separately, it’s tempting to think they represent different concepts that are opposed to each other.

That’s not the case. They’re actually closely related. As Teresa Torres points out, OKRs are a way of expressing an outcome.

It’s not a matter of OKRs vs outcomes. It’s how the two concepts work together and help you build a successful product.

To understand what that really means, it’s helpful to explore these concepts individually and then look at how you can use the two ideas in harmony to build your roadmap and guide your work.

What are Outcomes?

Outcomes describe what you’re trying to accomplish. Contrast that with outputs, which represent the things you deliver in order to accomplish something.

As you might expect, there are different types of outcomes based on the scope of what you’re trying to accomplish. Teresa Torres identified the two most meaningful types of outcomes: business outcomes and product outcomes.

Business Outcomes

When executives, and most product people, hear about outcomes their first thought goes to broad financial targets such as increasing revenue and profit and reducing costs. Think of these as business outcomes. Your overall business makes changes to increase revenue and/or reduce costs.

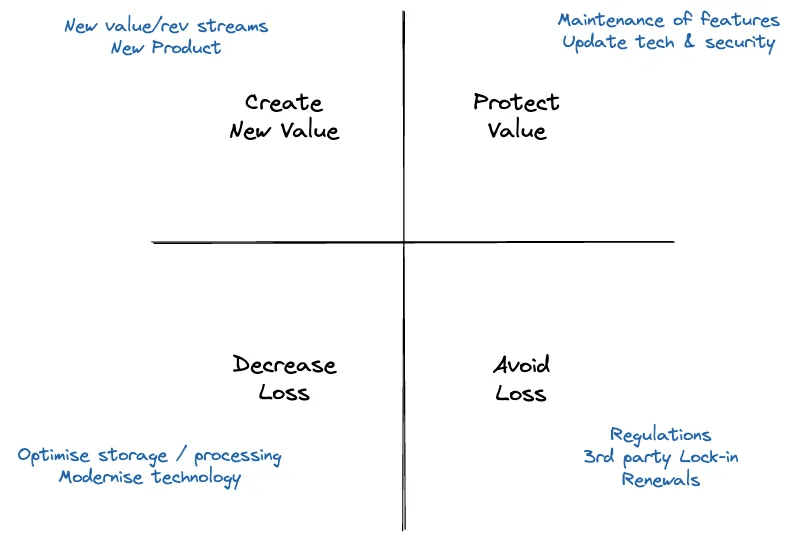

The developers on your product team, especially those steeped in agile software development approaches, may ask you how business outcomes relate to business value. They are, for all intents and purposes, the same thing. This model from Marcus Hamrin, a Senior Product Manager at Spotify, can help you think a little deeper about the different types of value and hence business outcomes.

Product Outcomes

More often than not, a single product team doesn’t work on something that directly leads to one of those four types of business outcomes.

So product teams need to identify things they can do that will change the behaviors of customers, users, or people inside the organization that ultimately lead to a change in business outcomes. Teresa Torres describes those as product outcomes.

Product outcomes are better for teams to use to measure progress because:

- Business outcomes, such as increased revenue, are lagging indicators. Once you can measure a change in revenue, it’s often too late to do anything about it.

- Product outcomes are leading indicators of business outcomes, which means they provide shorter feedback cycles and give you a chance to make changes.

- Product outcomes are within the influence of product teams. Contrastingly, business outcomes have too many variables involved.

The trouble with the concept of outcomes, or value for that matter is they are just that – concepts.

They’re vague. They’re obscure. They are great to talk about in theory, but how do you apply them in real life?

What are OKRs?

That’s where OKRs come into play. Like Teresa Torres explained, you can use OKRs to express your outcomes.

The O stands for objective. The KR stands for Key Results. To understand the concept at a high level, consider this formula for structuring OKRs from John Doerr, who introduced them to Google: (sourced from https://felipecastro.com/en/okr/what-is-okr/)

We will [Objective] as measured by [this set of Key Results].

Let’s look at the components of OKRs and how they relate to different levels of outcomes.

Objective

The Objective is a single sentence qualitative description of what you want to accomplish in the next month or quarter. Had OKR’s been invented in the last five years, the O probably could have stood for outcome, but it doesn’t.

Your objective should be short, memorable, and meaningful to the people who have to accomplish it. The objective also needs to be a stretch to accomplish, but not impossible, within the identified time frame.

Key Results

Key results explain how you’ll measure whether you’ve accomplished your objective. You want key results to measure outcomes (the change in a relevant measurement), not outputs (we deployed a particular feature).

Identify a small number of key results (usually around 3) so that you aren’t trying to track too many metrics.

Make sure to balance key results so that they represent potentially opposing forces. For example if your object is to drive growth, you may have a key result that measures revenue growth, but also establishes targets for quality and customer satisfaction. This key result set prevents you from taking reckless actions to grow revenue that have a detrimental impact on quality and customer satisfaction.

You can structure your OKRs in a way to gauge progress toward difficult to reach outcomes without completely discouraging your team in the process. Erica McKay, a Software Delivery Consultant at Lean Techniques, likes to represent key results as a set of numbers such as the following example she provided:

Objective:

We will enhance data transfer from corporate to customer and back as measured by:

| Key Result 1 | Key Result 2 | Key Result 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce time spent researching file transfer status | Increase success rate of file transfers | Increase adoption |

| 20% reduction | 20% success rate increase | 10% adoption increase |

| 50% reduction | 50% success rate increase | 30% adoption increase |

| 75% reduction | 75% success rate increase | 60% adoption increase |

| 95% reduction | 95% success rate increase | Full adoption |

At regular check points her team identifies where they are in relation to each key result. The bottom value in each list represents the ultimate target for that key result.

Erica explained, “I am not typically a fan of all or nothing which is why I use this approach. It allows us to gauge how well we are doing at hitting our goals as we incrementally deliver value.”

OKR Examples

So with that structure in mind, here’s how a product team at a wholesale company working on inventory service for their customers can represent a business outcome and corresponding product outcome with OKRs.

Business Outcome

Objective:

We will increase sales provided from our inventory offering as measured by:

| Key Result 1 | Key Result 2 | Key Result 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Increase sales from inventory offerings clients | Increase renewal rate for inventory offerings | Improve customer satisfaction score |

| 5% sales increase | 80% renewal rate | 80% customer sat |

| 10% sales increase | 85% renewal rate | 85% customer sat |

| 15% sales increase | 90% renewal rate | 90% customer sat |

| 20% sales increase | 95% renewal rate | 95% customer sat |

Product Outcome

Objective:

We will streamline new inventory location onboarding as measured by:

| Key Result 1 | Key Result 2 | Key Result 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce time required to onboard new locations | Decrease onboarding support tickets | Improve onboarding satisfaction score |

| 10% decrease | 20% reduction | 80% customer sat |

| 20% decrease | 50% reduction | 85% customer sat |

| 30% decrease | 75% reduction | 90% customer sat |

| 35% decrease | 95% reduction | 95% customer sat |

How to use OKRs in your Outcome Based Roadmaps

Now that your product team has expressed your product outcome in OKR form, you can use an outcome-driven roadmap to track the initiatives you will try to reach it.

Start with a roadmap with Now – Next – Later columns. The items in the Now column represent the specific experiments you’re currently working on in order to accomplish your targeted product outcome. As you deliver each of those items, you can gauge their success by checking the resulting value of the key results.

The items in the Next and Later columns represent the hypotheses you want to try next to reach your product outcome. You don’t identify experiments for those items because you may find you don’t need to test some hypotheses, or you may identify new hypotheses based on the results of the initial experiments.

If you’ve identified multiple product outcomes, you can track initiatives intended to drive progress toward a specific product outcome by color coating the initiatives by product outcomes on your roadmap.